TAMPA, Fla. (Sept. 22, 2015) – Wandering through a friend’s old and abandoned family palace in Spain in the summer of 2012, David Arbesú was surprised to discover long-neglected boxes of old documents. Part of the private archive of the Marquis of Ferrera in their home province of Asturias, the treasure trove was in danger of being destroyed by the ravages of leaks, humidity and time. Among them was an unknown manuscript which ended up being the most reliable and complete account of Pedro Menéndez de Avilés’s landing on Florida and the founding of St. Augustine 450 years ago.

The palace where the manuscript was found was built around the Torre de Bascones (Tower of Bascones) dating from the 13th or 14th century. Some records claim the 12th century.

The handwritten title in neat flowing script, “The Conquest of Florida by the Adelantao Pedro Menéndez de Valdes” told him this was an important volume. “I did not know if it was an all-new account of the conquest and settlement of Florida or a copy of one of the three main narratives we already knew of,” he said. (Adelantado is a military title held by some Spanish conquistadores.)

Menendez’s exploits were first reported on by his own brother-in-law, Gonzalo Solís de Merás. His manuscript tells of the capture of Fort Caroline, the infamous massacre of the French Huguenots at Matanzas Inlet, Menéndez’s exploration of the Florida river system, and his dealings with several Indian tribes of the Florida peninsula.

“As it turns out, the Ferrera manuscript is the second and most complete textual witness written by Solís de Merás and it supersedes the known Revillagigedo copy,” said Arbesú. “For a long time the Revillagigedo manuscript was the only known copy, which all editions of this work have followed. The Ferrera manuscript is the exception.”

Of all the people who could recognize the value of family papers long taken for granted, the Ferrera family was fortunate to have Arbesú for a friend. There are still people who love the feel of centuries-old handmade paper and who delight in reading ancient cursive writing. Arbesú is one such person among the dwindling number of experts of his kind. And, as it turns out, medieval manuscripts are the specialty of this archival researcher, along with early editions, codicology – that is the study of physical characteristics of books and manuscripts – and paleography, the study of handwriting. An assistant professor of Spanish in the Department of World Languages at USF, Arbesú teaches courses on Medieval and Renaissance Spain, as well as on the early history of Florida.

A Nick of Time Find

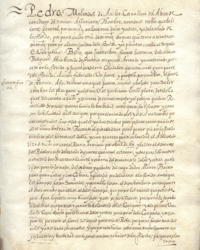

“The manuscript is in very

good condition,” he observed. “It is in a clear script, it is not lacking any

folios and its contents are displayed in the correct order.”

A page from the Ferrera manuscript.

Realizing what he had, Arbesú made his discovery essentially in the nick of time and he is perfectly situated to make the most of it. St. Augustine is the oldest European mainland settlement in what is today the United States, and celebrates a milestone birthday this September. Ponce De León and Menéndez were in effect the founding fathers of colonial Florida. Menéndez reached the coast of Cape Canaveral on 28 August 1565, the feast day of St Augustine of Hippo.

Arbesú learned that the manuscript’s scribe was a citizen of Madrid named Diego de Ribera.

“We do not know where Ribera came across this account of Pedro Menendez’s expedition, but it appears that he enjoyed it so much that he decided to investigate ‘what all these things amounted to and how it all ended,’ as he wrote, transcribing the chronicle together with a description of the land of Florida and several letters and royal edicts pertaining to the titles conferred upon the Adelantado by King Philip II. According to his own testimony, this was all he could find regarding these matters, and his sole purpose was no other than to provide us with a narrative that would please anybody who read it.” Ribera finished the work May 16, 1618.

This is not Arbesú’s only find. He located other important manuscripts related to Doña Mayor Guillén de Guzmán, King Alfonso X’s lover for whom he built a monastery. Long sought after, they came from the village of Alcocer in Guadalajara, Spain and are now owned by the Hispanic Society and the Massachusetts Center for Renaissance Studies.

Go to Arbesú’s office and you’ll find shelves of a great many very old documents – none nearly as important, but cherished nonetheless. Their rough handmade textures and black ink inscriptions instantly transport one to a time when literacy was a rare and precious commodity. Most come from the numerous markets in Europe that trade in ancient writings of all kinds – correspondence, both business-related and personal, and general business records as well as books. He knows them well.

“Tracking down old manuscripts in archives, libraries and public markets can be a frustrating and time-consuming activity, but, if you keep searching, you are bound to find something important every two to three years,” Arbesú said.

Arbesú is a contributor to numerous peer-reviewed journals including “Hispanic Journal,” “Bulletin of Spanish Studies,” “Hispamérica,” “Hispanófila,” “Tirant,” “Cervantes,” and “La corónica,” and frequently writes book reviews for them as well as for “Speculum, the Journal of the Medieval Academy of America” and “Manuscripta: Journal for Manuscript Studies.”

His books include a study and critical edition of Spain’s 14th-century version of “Floris and Blanchefleur,” a verse translation of “Don Juan Tenorio.” Arbesú is also the editor of the oldest translation of the Bible from Hebrew into Old Castilian, the “Fazienda de Ultramar.”

Adding Spain to the National Identity

The Marquis de Ferrera’s documents are now safely stored and Arbesú is still excited about this extraordinary find.

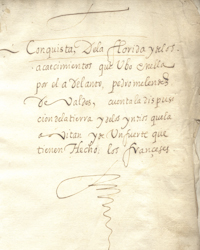

Another leaf from "The Conquest of Florida."

“With the discovery of this manuscript, we finally have a complete account of the exploits of Pedro Menéndez in Florida,” he said. Arbesú publishes his translation and introductory analysis early next year after St. Augustine’s birthday celebration this month. He hopes the manuscript, which he is titling “The Conquest of Florida,” will “help restore the figure of the Adelantado to his rightful place in the pages of the history books.”

He realizes though that this might be hoping for too much.

“The national identity of the United States is not rooted in Florida, but in the northern colonies. Thus, Pedro Menéndez is seldom studied in the United States as a ‘founding father’ of the nation, for he was not from the British Islands and his field of action was not New England.”

He’ll keep looking for written treasures. Manuscripts turn up in all kinds of places, among them the walls of houses.

“Many are discovered in the destruction of old houses,” Arbesú said. “Paper was used as insulation.” He went on to lament the fact that, “It’s hard to imagine how many are simply destroyed.”

People interested in following in Arbesú’s professional footsteps should know, “you have to know linguistics and history – historical linguistics.” And you have to have great patience. He is one of the very few Spanish paleographers in the United States, although he has been trying hard to increase students’ interest in paleography and archival research.

“To me, there is nothing more rewarding than finding a document that no one has read in several centuries. To be able to decipher and interpret its contents for the modern reader is what makes me think I have contributed something to the world.”

Barbara Melendez can be reached at 813-974-4563